What Does Dying Mean to a Five Year Old?

January 5th, 1969 was a date that forever changed my family. The grief of that date has affected me since I was five years old. It comes calling as the holidays approach like a damp blanket, an uninvited guest that exudes a palpable sadness and silent misery.

Each year as Christmas nears it shifts from the periphery and hangs over my shoulder. It breathes down my neck, uncomfortably close to my side. I make the most of the seasonal festivities with family and friends. I decorate cook and go to parties but this is not my favorite holiday and I feel a wave of relief when it is over.

Samuel Harold Shepard was the second son of Bertha and Samuel Shepard born at home on December 15th, 1923 in the foothills of the Smoky Mountains, Franklin North Carolina.

Sam came to Michigan after serving in the war. He worked as a bump and paint man fixing automobiles. He met my mom and their attraction was undeniable, every old photo confirms it. They would dress up for parties and wear silly homemade costumes. Many pictures show them laughing or looking at each other with grins and twinkling eyes. Together they built a life, raised four daughters and created a home of love and happiness.

What does dying mean to a five year old? Before his diagnosis my dad went to work each day, came home for lunch and was always busy with projects around the house. Now he was gone for days to the hospital. At home he was in bed or in a chair, cared for by my mom and oldest sister.

Dad was ill for a year. A tall thin man all his life now gaunt and skeletal, ravaged by cancer and the crude treatments of the 60’s. Being five I understood he was sick but knew nothing of the inevitable outcome of his disease.

Nearing the end of his life the hospital allowed him to come home for our last holiday as a family. I wish I remembered feeling joy and anticipation of Christmas morning, but that was not the case.

One evening as I watched from out of sight my grandpa Bill knelt beside my dad as he lay on the couch too weak to sit up. Grandpa, usually a stoic man, had tears streaming down his face. He promised my dad that he would take care of his girls.

It was gray and rainy the day the ambulance arrived at our home. The driver backed into our garage so dad would not get wet from the downpour. We watched the two men bring him out on a gurney from our living room. Dad lifted himself up and put a hand on each side of the door frame completely stopping the gurney and the men in their tracks.

At that moment, although I was only five, I realized he did not want to leave us - dad wanted to stay home. The men gently and silently settled him on the gurney and then he was gone. That was the last time I would see him alive.

Several days passed by and when I asked where my dad was, the response: ”He is going to heaven to see Jesus” confused me. I imagined him climbing stairs that led high up into the clouds to be with Jesus. But what did that mean? Would he be climbing back down at some point? Could I find the stairs and go up there too?

After a year of debilitating illness my dad’s life ended on January 5th, 1969 at the age of 45 by lung cancer. My mom was 38 years old and became a widow with four daughters. For me his death brought an unspoken sadness and the loss of a secure and carefree childhood.

At five years old I had no concept of death. When I saw my dad laying in his casket at the funeral home I thought he was sleeping. I didn’t realize it was permanent. I ran around the casket thinking it was a game we were playing; pulling myself up on tiptoes to look in at him and wondering why his face was frozen.

Things were different back then. People dying in the 60’s were “put away” in hospital rooms where visiting hours were limited and 5 year old children were not allowed. This experience profoundly impacted me and my attraction to working in end of life care.

My dad’s parents, my granny and pa lived in North Carolina and were still in a time and place of home wakes and home funerals. Up until the mid 1940s the community took care of the dead and their families. Death was a part of life. Babies were born at home and loved ones died there as well.

Granny would send us photos of dead relatives “laid out” in their home parlors, in their coffins prior to their burials. At the time we thought this was very strange. But working in hospice and becoming a death doula and advocate for home funerals, I find this memory extremely comforting. Oh how I wish I could speak with my granny now!

I asked my cousin Rita who explained the whole community was involved. Having lived down south her entire life she said when she was little her grandfather was a carpenter and always had a coffin cut out and ready to be put together, tucked up in the rafters of a barn.

In the old days, when someone died the family would get word to the church. The church would “toll the bell” which is a lower tone for each year of the deceased person’s life. Everyone in the area, whether they were working the fields or with the animals would hear the low sounding bell and count the number of rings to know the age of the person who died. Rita’s grandfather would begin building the coffin. If there weren’t many tolls of the bell and the person was a child, the coffin would be small.

The women in the community would make food to take to the family of the deceased. The body was washed, dressed and laid out for neighbors and friends to pay their respects and share stories of remembrance. The deceased would then be driven to the cemetery for burial.

I believe these final acts of service help with our grieving process; having the person die at home, washing and preparing the body, making the coffin, bringing food and sharing stories, carrying the coffin out of the house, digging the grave and putting the body in the ground. Each are ways we can participate in the death of our loved ones.

Some may not be comfortable with any of these ideas and that is okay. There are many ways to honor a loved one's passing. Death is something we shouldn’t be afraid to discuss. We need to come to terms with it, to be comfortable around it. There is peace in knowing what those closest to you would prefer when they die.

Living with grief is something we all do to varying degrees in our lifetime but we don’t talk about it. Through my education in death care I realize that grief has no expiration date and everyone's grief is unique to them. We would do better to talk less and listen to each other more - even if it means hearing anguish and pain from someone you love. The act of listening validates a person’s grief. It doesn’t make it disappear but it helps them to move through their loss.

My grief was surely compounded by the fact that I knew in my heart my dad wanted to be at home until the end of his life. Being five years old I wasn’t able to advocate for myself let alone my dad. I spoke with my mom years ago about my memory and the pain she expressed helped me understand her sorrow as well.

I’ve carried this story for 54 years without fully acknowledging the monumental loss of my dad. Twenty seven years later my grandpa Bill came to our home to die on hospice. I understand now why I felt a deep need to fulfill my grandpa’s wish to be home with family.

Although I am still sometimes sad about losing my dad, I feel gratitude and peace that I was able to fulfill my grandpa Bill’s dying wish. In telling this story I realize that I honored them both by taking care of the man that promised my dad he would take care of me.

Blessings,

Shelley

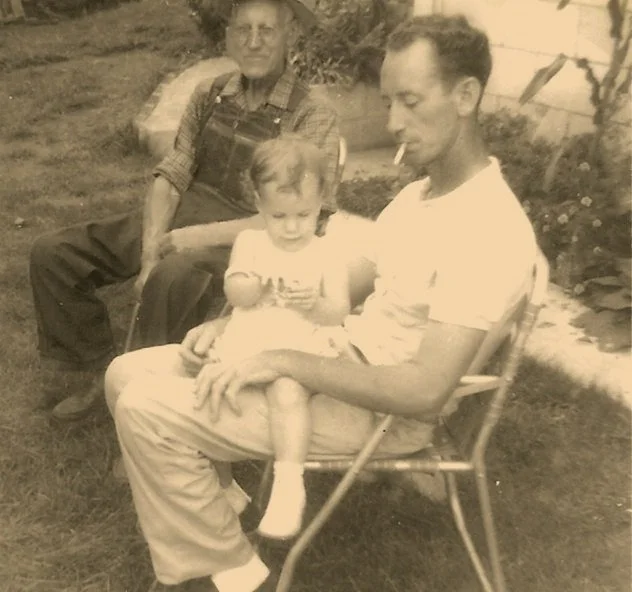

Me, my dad and pa in Franklin NC 1965